I. Sketch the Same Old Stuff Anyway

As I sit down to write this morning, Marz has likely finished her first day of walking the Camino. (Hi, Marz! Are you wearing your Crocs?)

BELOW: My first day, from my first Camino sketchbook, July 7, 2001

LEFT: bink looking like she has bad jetlag--not because I'm an amateur artist, but because she did.

RIGHT: I got the first of many blisters at the pass where Roland, a leader in Charlemagne's army, died in battle in 778, according to 11th century The Song of Roland.

At this point, you know you're not in Kansas.

I wish I'd kept sketching daily on Camino. I think I got bored of drawing feet and coffee cups...? I didn't appreciate that even mundane sketches are fun to look at later. (Photos, not so much.)

It's a challenge to draw what you see everyday. I'll take a sketchbook on my next walk--probably that'll be tomorrow, unless the air quality improves A LOT today. Smoke from Canada yesterday put us back in the red: "unhealthy for all groups"––I stayed home from work.

II. Consider the lilies...

Yesterday evening, the wind shifted and cleared the air somewhat, temporarily ––"Oh, good, it's only the yellow warning!"

I walked to the Turtle Fountain and took close-ups of lily buds:

This garden has an interesting history as part of an earlier era's push to make nice stuff for the sake of a healthy citizenry.

The idea being we would get better and better...

Part of the Lyndale Park Gardens, our garden was started in 1907 by park superintendent Theodore Wirth ("widely regarded as the dean of the local parks movement in America"), with the help of Louis Boeglin, the park board horticulturist.

(Hm, Wirth's Wikipedia page is rather scant--maybe I should improve that.)

III. The Praxis of Hope, Again

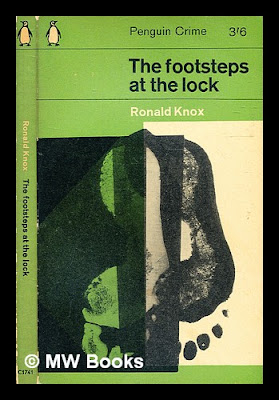

I'm reading God and the Atom (1945), written right after the US bombed Hiroshima, by the English writer Ronald A. Knox. ('A' for Arbuthnott--some girlettes are claiming this for a last name--it's a Scottish place name.)

Knox, who was fifty-seven in 1945, was the uncle of author Penelope Fitzgerald, author of The Bookshop, a favorite novel of mine. Fitzgerald was twenty-eight when the US dropped the atom bomb. Her first novel, The Bookshop, was published in 1978 when Fitzgerald was sixty-one.

(I have missed the deadline.)

From a 2014 article about Fitzgerald–– "Late Bloom"––in the New Yorker:

Penelope Knox was born into "a brilliantly clever English family distinguished by alarming honesty, caustic wit, shyness, moral rigour, willpower, oddness, and powerful banked-down feelings, erupting in moments of sentiment or in violent bursts of temper and gloom."I'd enjoyed Fitzgerald's bio, The Knox Brothers. (There were four.)

Her father's brilliant brother R. A. was a writer, theologian, priest (famously at the time, an Anglican convert to Catholicism), ... and an early influence on creative fandom. I put him in my fandom book! Specifically, on detective and Sherlock Holmes fandom. R.A. himself also wrote detective stories.

Knox starts God and the Atom with the moment of learning that the US had dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima:

"At a moment when it seemed as if all our capacity for surprise were already exhausted, one day last August, we opened the paper to find that we were wrong. ...

A Japanese town ... had suddenly ceased to exist.

Our first reaction, probably, was one of fear...

followed, in many minds, by a sense of shame.

...A very general bewilderment was registered, a moral bewilderment...."

Knox then wonders what I've always wondered, *

"Would

it not have been possible to introduce the new weapon by dropping in on

some unfrequented mountain-side,

and asking the Japanese whether they

wanted to go on with the war after that?"

Surely it was possible, but that's not what we did.

Knox talks about what a shock the bombing of Hiroshima was to the "let's build parks" sensibility that led to my Turtle Fountain park, spelling an end to the Victorian doctrine of progress:

that we were to harness

nature for our gradual social betterment--eventually arriving at Utopia.

Every day we were to get better and better... and then, WWI.

Bad, but hope remained, if tattered: it was to be the war to end all wars.

BELOW: The Menin Road, (1919) by Paul Nash

And then, WWII--also bad, very very bad, and then... BOOM!

There goes Utopia.

This happened on a social level in a specific time of history, but it can happen on a personal level in any individual's everyday life too. And, I think, what Knox writes applies, with changes where change is needed, whether you believe in a soul or a god or not. Or, his perspective helps atheist me, anyway.

Knox asks, "What then should be the posture of a soul which is submitted to this terrible ordeal [of feeling certain of doom]?"

Basically, he answers––toward the end of the book (after a whole lot of too much scholastic theology, most of which I skipped)––we should "go on behaving as if we hoped".

"Can a soul really hope, it may be asked, when the whole mind is overshadowed by the conviction that there is no hope at all? The best answer to that question is implied by a well known passage in the Imitation of Christ [early 1400s, Thomas à Kempis].

'There was a man that was tossed ever to and fro between hope and fear. One day, overcome with melancholy, he went into Church and threw himself down in prayer before one of the altars.

Ah, he thought to himself, if only I could be certain that I should go on persevering!

Whereupon he heard the Divine answer in his heart,

And if thou wert certain, what wouldst thou be doing?

Do now what thou wouldst be doing then, and thy anxieties will vanish.' "

[italics mine]

As we say now, "Act as if...".

Keep the public gardens.

And a sketchbook.

________

P.S. I was going to go into work this afternoon if the air quality improved, but it hasn't. So let me go on a little further. It's a good day to think about how to be hopeful when your eyes and throat are dry from distant fires...

IV. Humanitarian Utopianism

*"What

if the atomic bomb had been dropped on an unpopulated area instead of

on Hiroshima is the premise of Kim Stanley Robinson's short story, "The

Lucky Strike" (1984).

So, so good--one of my favorites.

OH--you can read "The Lucky Strike" here, reprinted online in 2014 by Strange Horizons magazine:

http://strangehorizons.com/fiction/the-lucky-strike

ABOVE: Kim Stanley Robinson, 2017, from article: "Kim Stanley Robinson: 'Science needs to think of itself more as a humanism and as an utopian politics'”

KS Robinson seems not to believe in god/s.

“Literature is my religion,” he said. “The novel is my way of making sense of things.

... In interviews he frequently speaks of the Zen rubric 'chop wood, carry water' and claims that it could just as easily be 'run five miles, write five pages.'” (via)

The New York Times actually described KSR as "utopian" last year (2022). When Robinson spoke at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, he was asked to predict what the world will look like in 2050.

"At 70, Robinson — who is widely acclaimed as one of the most influential speculative fiction writers of his generation — stands as perhaps the last of the great utopians."

Robinson, whose novel, The Ministry for the Future, lays out a path for humanity that narrowly averts a biosphere collapse, sounded a note of cautious optimism. Overcome with emotion at times, he raised the possibility of a near future marked by 'human accomplishment and solidarity.''It should not be a solitary day dream of a writer sitting in his garden, imagining there could be a better world,' Robinson told the crowd."

--"A Sci-Fi Writer Returns to Earth: ‘The Real Story Is the One Facing Us’", by Alexandra Alter, New York Times, May 11, 2022.

Yeah, so for me, this is encouraging because it's what I came to many years ago:

find good stories, share good stories, write/tell/make good stories.

Or, you know, bad ones. But stories!

It seems to me that when we dropped the bombs over Hiroshima, we signed our own death warrants as a race. We failed all the tests.

ReplyDeleteMS MOON; yes, but there’s hope, right? You chose to bring four children into the world—wasn’t each a choice for hope? (Or not?) Where did you find that hope?

ReplyDelete